Remembering Rangiaowhia: 150th Anniversary

21 February marks the 150th anniversary of one of the most painful and contentious incidents of the Waikato War. To call the British raid on the settlement of Rangiaowhia a ‘battle’ would be misleading. Most of the residents of the village were women, children and a few elderly men. Once British troops had bypassed the formidable Paterangi line of pa in the dead of night, Rangiaowhia remained more or less defenceless. It was attacked at the break of dawn on a Sunday morning, the fire from cavalrymen as they entered the village causing its startled occupants to run in terror in every direction. Some sought shelter in churches, others in their thatched whare. Some did not get away.

According to considerable Maori testimony, the makeup of its residents reflected Rangiaowhia’s status as a place of sanctuary for non-combatants. It was understood that some kind of message had been exchanged with British commanders, possibly through Bishop Selwyn, to this effect, as a result of which the British raid was considered an act of great treachery. After Rangiaowhia, Wiremu Tamihana later stated in a petition to Parliament, ‘I discovered that this would be a very great war, because it was conducted in such a pitiless manner.’

Of particular anguish was what appears to have been the deliberate torching of a whare in which at least seven people were burnt to death, along with the probable deaths of a number of women and children. It was later a matter of some embarrassment to military authorities that of the 33 prisoners rounded up in the aftermath of the attack, 21 were women and children, and the remaining 12 apparently elderly men. There are multiple and often contradictory accounts of the attack, and these need to be carefully handled. But the pain and anguish caused by the British attack remains all too evident a century and a half later. As Whitiora Te Kumete told J. C. Firth and Charles Davis in 1869:

Following the British attack on Rangiaowhia, the main body of Kingitanga defenders manning the Paterangi line abandoned their position, but suffered further heavy losses in their hastily constructed new defensive post at Hairini the next day.

According to considerable Maori testimony, the makeup of its residents reflected Rangiaowhia’s status as a place of sanctuary for non-combatants. It was understood that some kind of message had been exchanged with British commanders, possibly through Bishop Selwyn, to this effect, as a result of which the British raid was considered an act of great treachery. After Rangiaowhia, Wiremu Tamihana later stated in a petition to Parliament, ‘I discovered that this would be a very great war, because it was conducted in such a pitiless manner.’

|

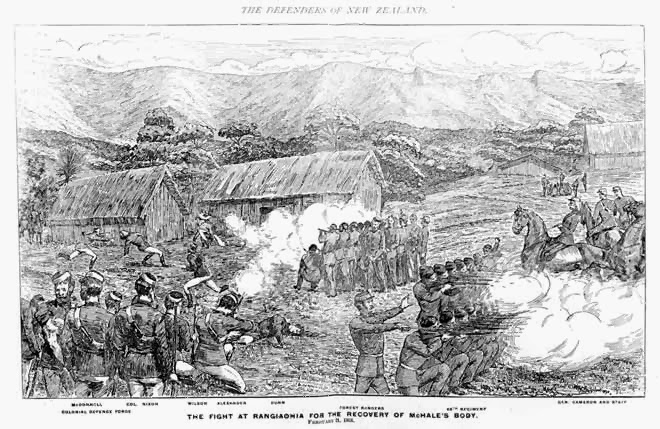

| The British Attack on Rangiaowhia (source: www.teara.govt.nz) |

here are your foul murders: - General Cameron told us to send our women and children to Rangiaowhia, where they should remain unmolested; but he went away from Paterangi with his soldiers after them, and the women and children were killed and some of them burnt in the houses. You did not go to fight the men; you left them and went away to fight with the women and little children. These things you conceal because they are faults on your side, but anything on our side you set down against us, and open your mouths wide to proclaim it. That deed of yours was a foul murder, and yet there is nobody to proclaim it. (AJHR, 1869, A-12, p. 12)

Following the British attack on Rangiaowhia, the main body of Kingitanga defenders manning the Paterangi line abandoned their position, but suffered further heavy losses in their hastily constructed new defensive post at Hairini the next day.

Comments

Post a Comment